1876

The Candidates

Samuel

Tilden

Democrat

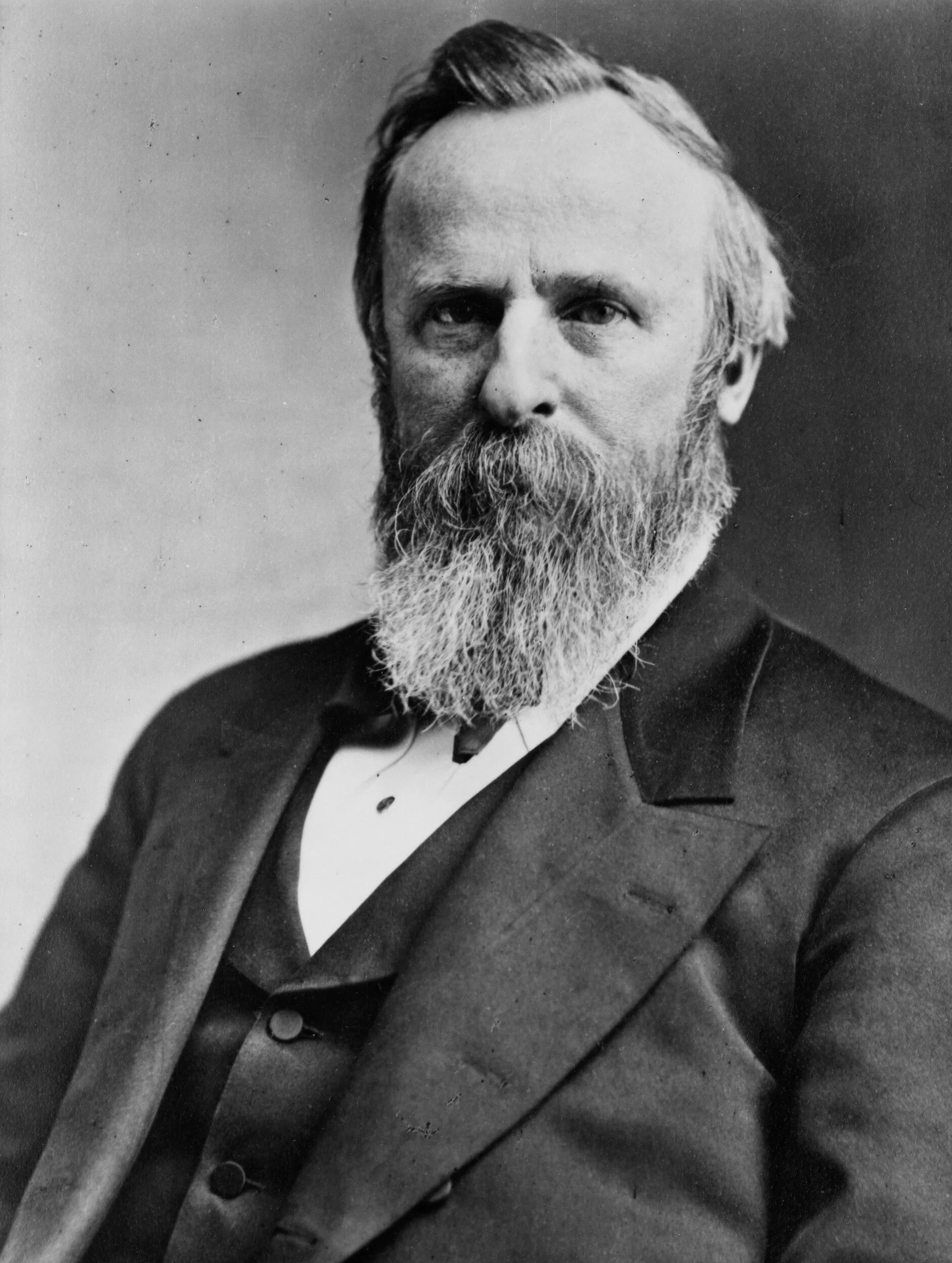

Rutherford

Hayes

Republican

Background

After the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, constant tribulations under Andrew Johnson, and corruption under Ulysses S. Grant, the post-Civil War revival of America had not gone well. America was moving beyond the old North-South divide to a new latitudinal division between the westward expansion of new railroads and the Eastern states trying to deflate the tensions still felt after the end of slavery.

President Ulysses S. Grant, a Union general and hero of the Civil War, was not a politician. In fact, Grant’s first public office was the presidency. The politics of post-Civil War Washington were an unforgiving place for a rookie, and Grant had his fair share of struggles. Despite the corruption then afoot, Grant’s administration managed to have a handful of successes. Namely, “the arbitration of the Alabama claims, the enactment of the Ku Klan Act, the veto of the Inflationary Act, and the successful prosecution of the Whiskey Ring, were all to his credit” (32).

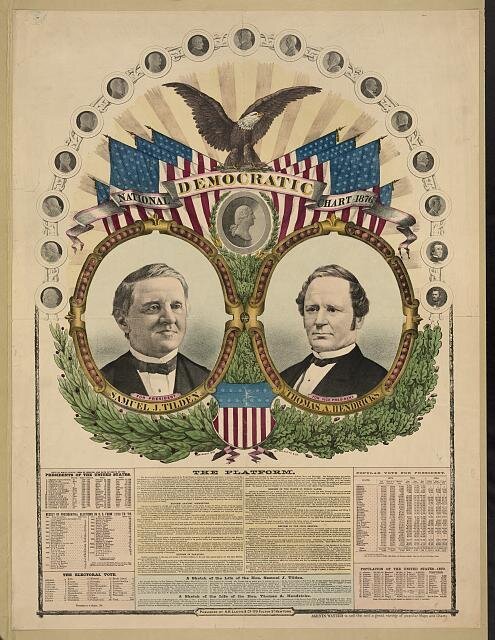

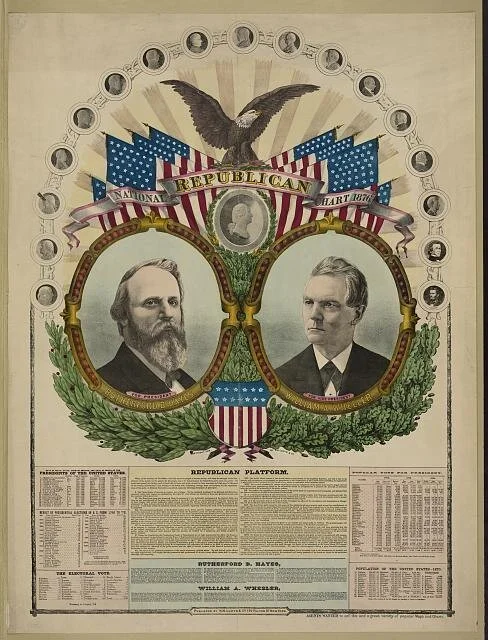

Democratic Ticket: Samuel J. Tilden for President and Thomas Hendricks for Vice President

Republican Ticket: Rutherford B. Hayes for President and William Wheeler for Vice President

Though the Grant administration did not fail to bring about any positive changes, the corruption and financial struggles toward the end of his presidency plagued the Republican cause in Congress. In the last midterm during Grants’ second term, Republicans lost 10 seats in the Senate and 96 in the House. The Senate Republicans held on to an 18-seat edge, but Democrats in the House had gained 96 seats and now had a 79-seat majority. This was the 44th Congress the next president would have to deal with. Determining who that next Chief Executive would, however, prove to be the most unorthodox presidential election in U.S. history.

Issues of the Day

Slavery

One of the most pressing issues of the day was how to reconcile the divide over slavery between the North and South. Even though the 13th and 14th Amendments had been ratified emancipating slaves and giving African-American men the right to vote, little changed in the minds of Southerners. It was this fact that made Republicans fear that “if there were no constitutional protection for the newly freed slaves, the governments of the former Confederate states would be controlled by the same white oligarchy responsible for secession–with dire consequences for the former slaves” (46). Moreover, how was the North to go about readmitting the formerly Confederate Southern states who had seceded? When the southern states seceded, they left their Congressional offices in D.C. too. The Congress that convened in 1865 had 136 Republicans and 38 Democrats. (The Republicans would hold onto a majority in the House until 1875 after the Panic of 1873). Under Congressional Republicans’ Reconstruction plan, Southern states would be readmitted to the Union once they had ratified the 14th Amendment. This was a prerequisite to any consideration of admission. It was non-negotiable. African Americans needed protection from the discrimination they would undoubtedly face and the 14th Amendment was seen as that shield.

The society emancipated slaves entered after the Civil War was vexing, to say the least. Half the country had fought to end slavery and the other had fought to keep it. Southern whites were still disgruntled at what they saw as an unjust expansion of the federal executive and imposition of Northern industrial morality. Northerners were tired of the South’s antics. And poor white laborers were also adamantly against slavery not only on moral grounds but also economic ones. It was impossible to compete with the free labor of the Southern slaves.

There were also bipartisan concerns over states’ rights in the Reconstruction era. For instance, in an effort to protect African-American men from the continuing harassment, intimidation, beating, and hanging of African-American men at the polls who had the gall to vote, Republicans in Washington sent federal troops to oversee polling stations. These efforts were not initially as effective as had been hoped, so “when Congress convened in March 1871, [President] Grant requested legislation aimed directly at the Klan,” the worst perpetrator of poll intimidations (18). Against the protests of the Democrats in the House (still a 32-seat-minority) and a growing distaste for the interventionist policy even in the North, the bill passed making “it a crime to conspire to prevent persons from voting, holding office, or otherwise enjoying equal protection” (18). The bill was “remarkably successful,” further angering Southern Democrats who knew this would jeopardize the gains they had been making in Congress (18). Their fears were well-founded.

In the next election in 1873, Republicans gained 63 seats (primarily in Southern states) while Democrats lost 16 seats. The Senate was under Republican control for the first three years of the Hayes presidency. This minority status would soon be eviscerated just two years later in the wake of the Panic of 1873 and the Credit Mobilier scandal (24). The Democrats blew out the 1875 midterms gaining 96 seats while Republicans lost 96 seats. It was this new and empowered Democratic majority that ran the House of Representatives during the election of 1876. This 79-seat Democratic majority was responsible for demanding that Hayes withdraw federal troops from the South in exchange for allowing him to enter office, and it ensured that Hayes’s first years in office would be no walk in the park.